1. Context and motivation

ISR has been developing computer-vision systems for real industrial environments for many years. We work daily with production lines that involve demanding cycle times, high product variability, strict quality requirements and, increasingly, the need for explainability. In this context, one question arises again and again:

Is artificial intelligence alone enough, or does classical machine vision still play a relevant role?

Based on our experience across multiple sectors and applications, the answer is clear: hybrid architectures, which combine classical vision techniques with neural networks, represent one of the most robust, efficient and scalable approaches in industrial vision today.

2. What we mean by hybrid architectures

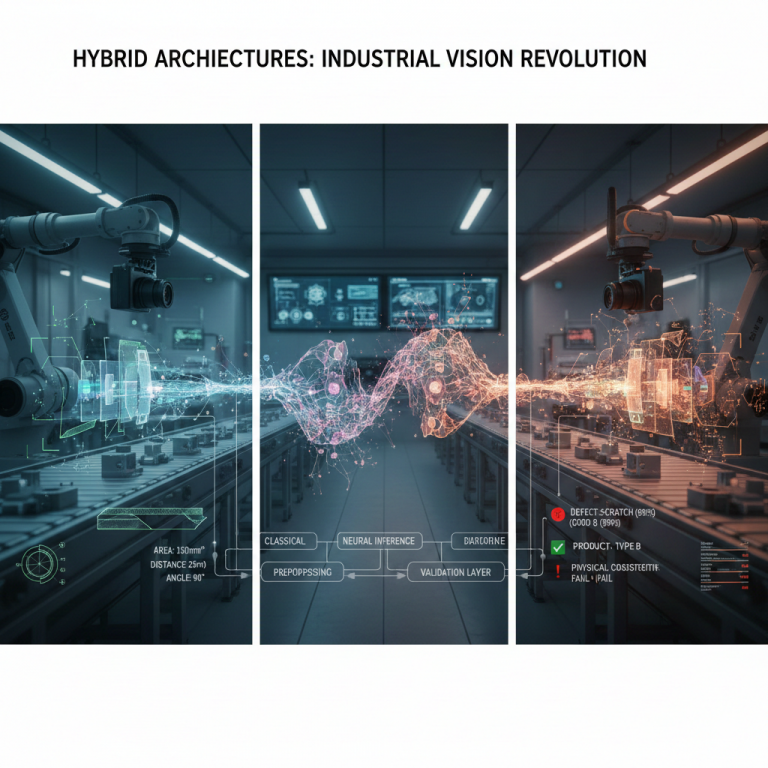

Hybrid architectures refer to systems that deliberately combine classical computer-vision algorithms—based on geometry, optics and image processing—with deep-learning models, typically convolutional neural networks.

The goal is not to replace one technology with another, but to leverage the strengths of both. Classical vision provides control, determinism and interpretability, while neural networks add adaptability and robustness in the presence of variability and complex visual patterns.

3. Classical machine vision: still a cornerstone

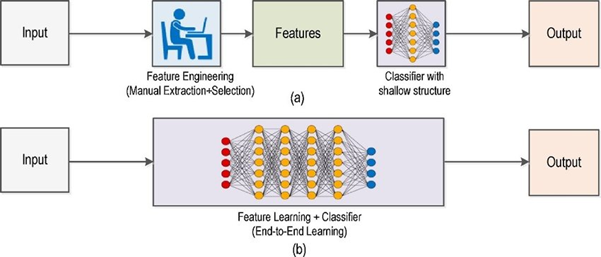

Before the rise of deep learning, industrial vision systems relied almost entirely on techniques such as thresholding, color segmentation, morphological filtering, edge and contour detection, geometric measurements, and texture or reflectance analysis.

These techniques remain highly valuable in industrial contexts because they offer low computational cost, deterministic and repeatable behavior, high explainability, ease of debugging, and precise tuning by process and vision engineers. Their limitations appear mainly when systems must handle non-trivial variability, such as changing illumination, heterogeneous raw materials, poorly defined defects or open-ended scenarios.

4. Neural networks: power against variability

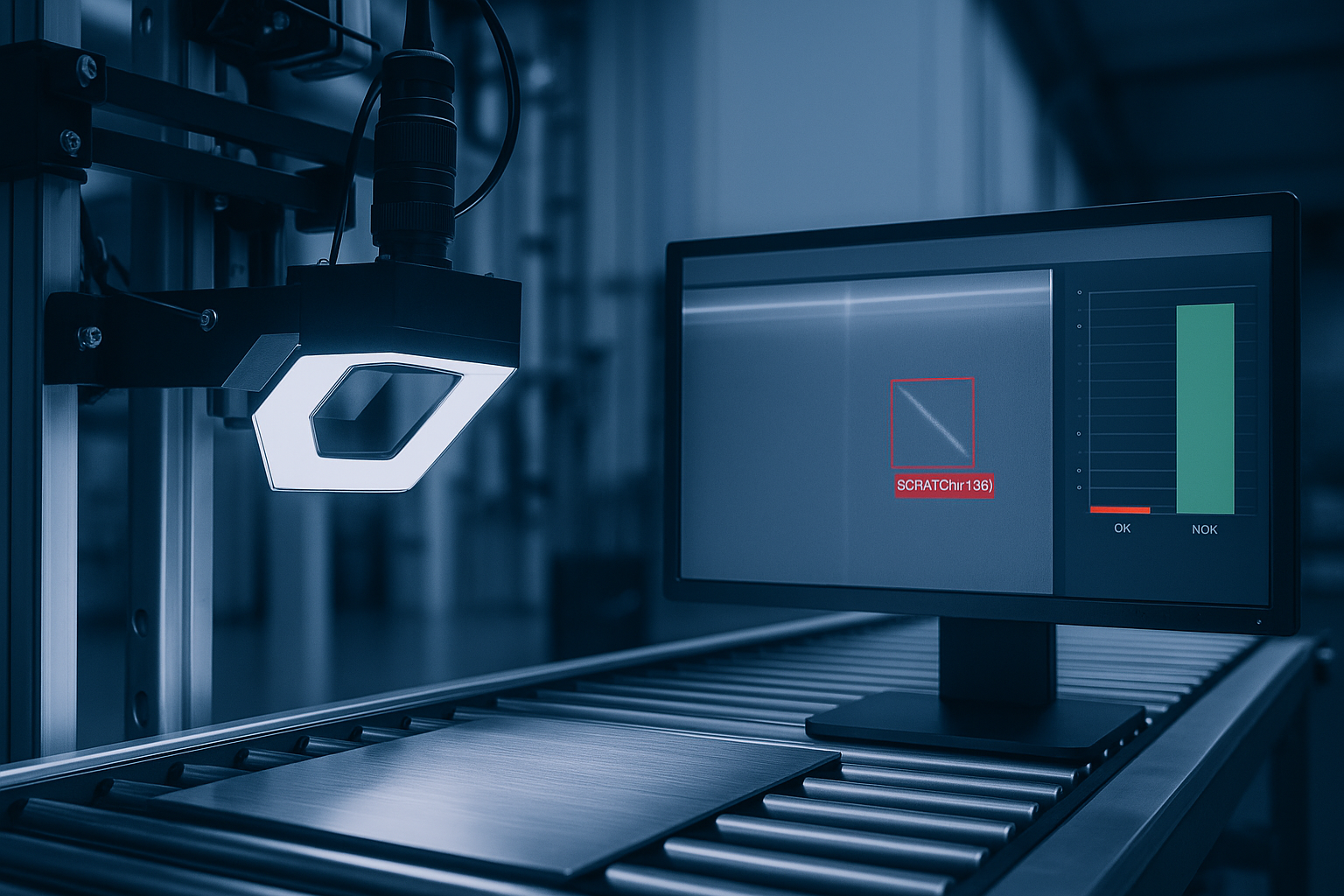

Modern neural networks have proven extremely effective for detecting complex or subtle defects, classifying products with high variability, and learning patterns that are difficult—or impossible—to describe with explicit rules.

In real industrial deployments, however, they also introduce challenges. They require representative and well-curated datasets, their decisions are often harder to interpret, they may introduce unnecessary complexity for simple problems, and they can be sensitive to domain shifts outside their training data. For this reason, at ISR we deliberately avoid an “AI-only” mindset.

5. The hybrid approach: assigning the right tool to each task

A well-designed hybrid architecture assigns each processing step to the most appropriate technology. Typical and proven patterns include:

5.1. Classical preprocessing followed by neural inference

Where classical vision stabilizes and normalizes the image—through illumination normalization, background removal or geometric correction—before feeding it to the neural network. This improves robustness and reduces data requirements.

5.2. Neural detection combined with classical measurement

In which the neural network identifies where to look, while classical vision performs dimensional measurements, computes ratios or percentages, and verifies tolerances, increasing accuracy and traceability.

5.3. Classical rules as a validation layer

Applying physical or geometric constraints, feasibility checks or cross-validation between sensors after an AI decision, significantly reduces critical false positives in production.

6. Key benefits in industrial environments

From ISR’s project experience, hybrid architectures provide clear advantages: increased robustness against process variability, reduced dependency on very large datasets, improved explainability for customers and audits, optimized cycle time and computational efficiency, and easier maintenance and long-term evolution.

They also enable artificial intelligence to be introduced gradually and safely, which is essential in critical production lines where existing systems must remain stable.

7. Beyond algorithms: a system-level vision

Hybrid architectures are not just an algorithmic choice, but a design philosophy. They require deep understanding of the industrial process, physical knowledge of products and materials, proper selection of sensors and illumination, and modular, maintainable software architectures. Artificial intelligence is treated as a tool, not as an end in itself.

At ISR, machine vision is approached as a complete system rather than an isolated neural network.

8. Conclusion

The key question today is no longer whether to use classical vision or artificial intelligence, but how to combine them intelligently to solve real industrial problems.

Hybrid architectures represent one of the most solid and pragmatic ways to bring computer vision and AI into production environments with reliability and confidence. At ISR, we continue to develop solutions where engineering, physics and artificial intelligence work together—because that is where truly robust and productive systems are built.